What Is PDCA? The Plan-Do-Check-Act Cycle Explained

February 6, 2026Continuous improvement doesn’t require complicated frameworks to be effective. One of the simplest and most enduring models for improvement is the PDCA cycle. PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) is a continuous improvement cycle used to test changes, learn from results, and refine processes over time.

At its core, PDCA treats improvement as a series of small, structured experiments rather than a single, large-scale initiative. The PDCA cycle is used across industries as a way to reduce risk, encourage learning, and improve outcomes incrementally. Whether you’re improving a production process or refining how a team works, PDCA provides a repeatable way to turn ideas into measurable improvements.

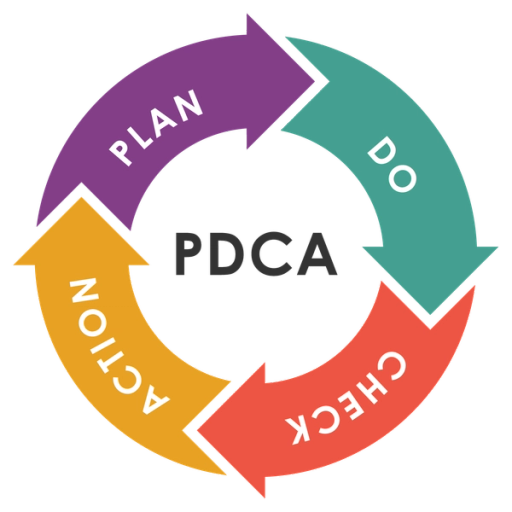

What Does PDCA Stand For?

PDCA stands for Plan, Do, Check, Act. It describes a continuous improvement cycle designed to test changes on a small scale, evaluate results, and standardize successful improvements.

- Plan – Identify a problem or opportunity, define objectives, and develop a hypothesis for improvement

- Do – Implement the change on a small scale

- Check – Measure results and compare them to expectations

- Act – Standardize the improvement or adjust and repeat the cycle

Rather than treating improvement as a one-time event, PDCA encourages ongoing experimentation and learning. By testing ideas on a small scale before standardizing changes, teams reduce risk and gain confidence that improvements will actually deliver the intended results.

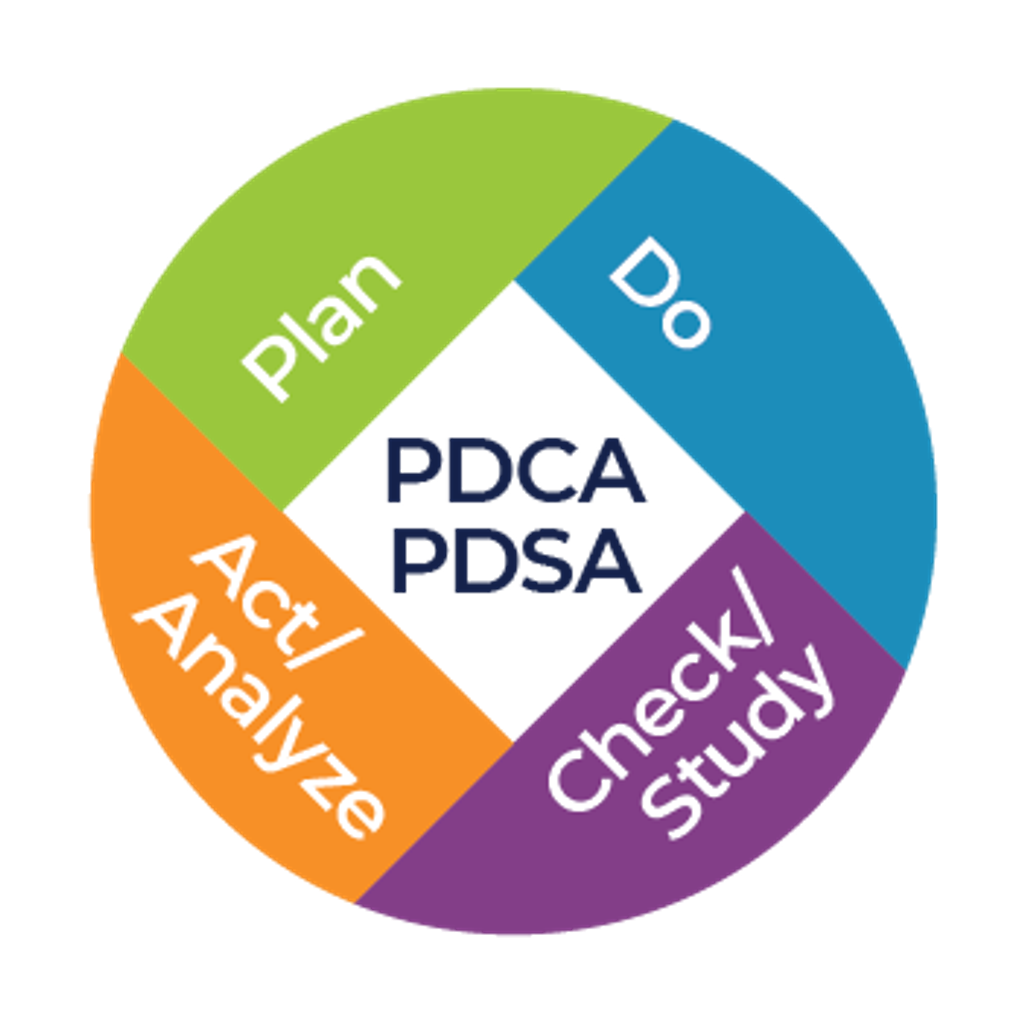

PDCA vs. PDSA: What’s the Difference?

You may also see this cycle referred to as PDSA—Plan, Do, Study, Act.

The difference is largely philosophical rather than practical:

- “Check” implies verification or inspection

- “Study” emphasizes learning, reflection, and analysis

W. Edwards Deming preferred PDSA because it better reflects the intent of the cycle: understanding why results occurred, not just whether a target was met.

In practice, PDCA and PDSA function as the same improvement cycle. Organizations frequently use the terms interchangeably, and both emphasize learning, evidence, and thoughtful adaptation over simple inspection. When PDCA is used well, it naturally incorporates the “study” mindset Deming advocated, even if the language remains Plan-Do-Check-Act. If you’re using PDCA effectively, you’re likely already practicing PDSA, even if the name differs.

If you’d like to dig deeper into Deming’s perspective on PDSA versus PDCA, the Deming Institute’s Circling Back: Clearing Up Confusion About PDSA and PDCA offers a thoughtful and detailed explanation.

Where Did PDCA Come From?

The origins of PDCA trace back to Walter Shewhart, who introduced early ideas around statistical control and iterative learning while working at Bell Labs in the early 20th century. Shewhart’s work emphasized the idea that improvement should be approached as a cycle of prediction, testing, and learning rather than a one-time fix.

These ideas were later expanded and popularized by W. Edwards Deming, who brought the improvement cycle to prominence through his work in postwar Japan. Deming emphasized feedback, reflection, and learning as essential elements of quality improvement. He shifted the focus from inspection to understanding and improving processes.

As a result, PDCA became deeply embedded in Japanese manufacturing and management practices, most notably influencing the Toyota Production System. From there, it evolved into a foundational concept behind modern Lean and continuous improvement approaches across industries.

Today, PDCA remains a cornerstone of improvement thinking precisely because of its simplicity and adaptability. Its principles apply just as readily to factory floors as they do to offices, hospitals, and other environments where learning and improvement matter.

How PDCA Fits Into Lean Six Sigma

PDCA underpins many of the structured improvement methods used in Lean and Six Sigma, even when it isn’t explicitly named. At its core, PDCA represents the basic logic that drives improvement: plan a change, test it, learn from the results, and act on that learning.

Many well-known Lean and Six Sigma approaches are built on this same cycle, but with additional structure and rigor layered on top. Methods such as DMAIC, A3 Problem Solving, Kaizen events, and Root Cause Analysis all follow the same fundamental pattern of planning, testing, evaluating, and adjusting. Each one simply emphasizes different tools, levels of analysis, or time horizons.

While these frameworks provide discipline and consistency for larger or more complex problems, PDCA remains the underlying engine that makes them effective. Whether applied informally by a team or formally through a defined methodology, PDCA provides the learning loop that turns data and experience into sustained improvement.

Want to learn more about all the different process improvement roadmaps? Check out Problem-Solving Roadmaps: Definitions, Examinations, and Common Myths Explained.

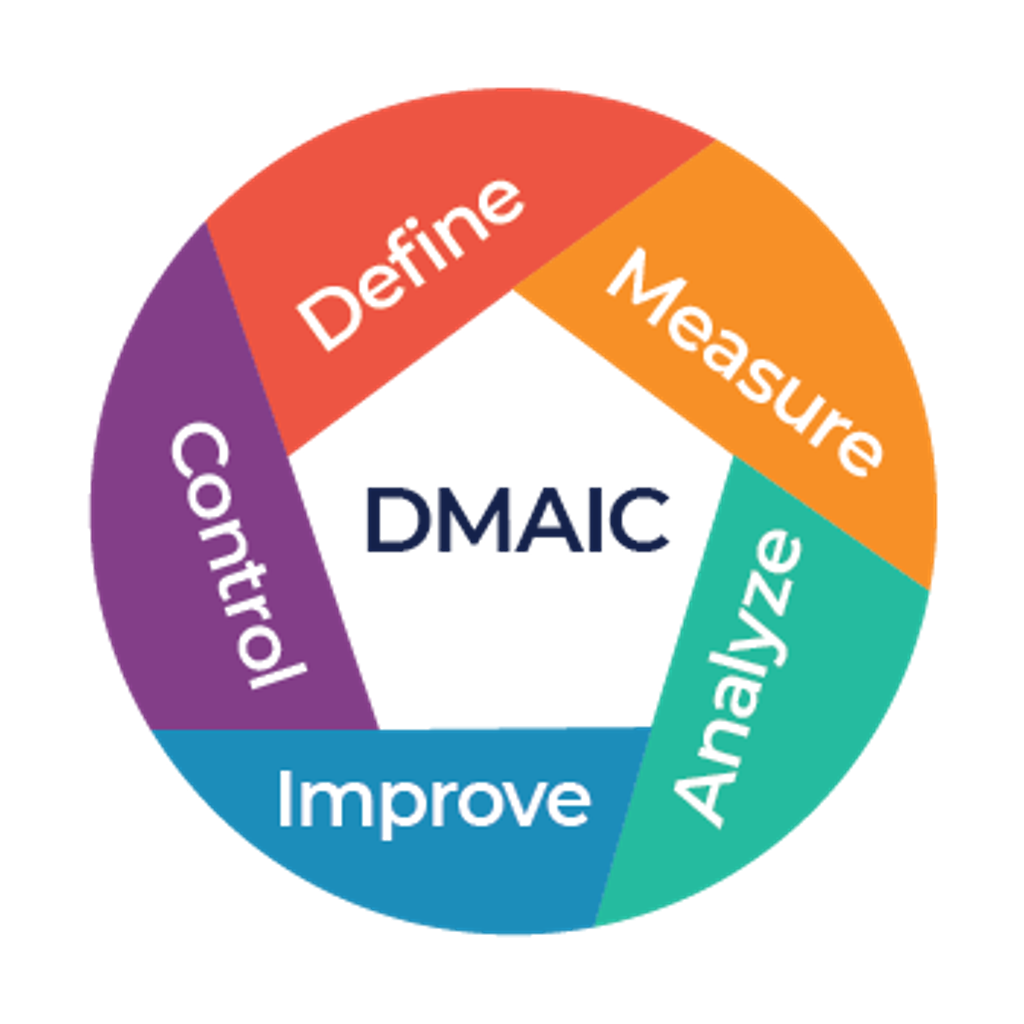

PDCA vs. DMAIC: What’s the Difference?

PDCA and DMAIC are closely related improvement approaches, but they’re designed for different situations. Both follow a structured logic for solving problems and improving processes, yet they differ in level of rigor, speed, and intent. Understanding how they relate helps teams choose the right tool for the job.

PDCA: A Lightweight Cycle for Learning and Iteration

PDCA is a flexible, iterative cycle focused on learning through experimentation. Teams use PDCA to plan a change, test it on a small scale, study the results, and then act based on what they learn. The emphasis is on rapid feedback and continuous adjustment rather than exhaustive upfront analysis.

Because of its simplicity, PDCA works especially well for day-to-day improvement, incremental changes, and situations where learning quickly is more important than statistical certainty. It encourages teams to test ideas safely, reduce risk, and build momentum through small wins.

DMAIC: A Structured Framework for Complex Problems

DMAIC is a more formal, data-driven framework commonly used in Six Sigma initiatives. It guides teams through defining the problem, measuring current performance, analyzing root causes, implementing improvements, and controlling the process to sustain gains. Each phase has specific objectives, tools, and deliverables.

DMAIC is best suited for complex, high-impact problems where the root cause is unclear, variation must be quantified, or decisions need to be supported by robust data. While it takes more time and effort than PDCA, DMAIC provides rigor and confidence when the stakes are high.

Rather than competing approaches, PDCA and DMAIC complement each other. PDCA often supports continuous, everyday improvement, while DMAIC is reserved for larger, cross-functional challenges that require deeper analysis. In many organizations, PDCA serves as the improvement mindset, with DMAIC applied when additional structure and validation are needed.

Both rely on the same fundamental principle: improvement comes from planning thoughtfully, testing changes, learning from results, and acting on that learning.

If you’d like to learn more about DMAIC, explore our blog: What Is the DMAIC Methodology?

How PDCA Works in Practice

In practice, PDCA functions as a structured experiment rather than a rigid checklist. Consider a manufacturing team trying to reduce changeover time on a production line. During the Plan phase, the team identifies excessive downtime between runs, sets a clear objective, and develops a hypothesis, such as adjusting setup sequencing or tool placement.

In the Do phase, the team tests the change on a limited scale, perhaps on a single shift or machine, while carefully documenting what was changed and any unexpected issues. Rather than rolling the change out broadly, PDCA encourages small, controlled tests that limit risk.

Next, during Check, the team evaluates whether the change reduced changeover time and improved throughput as expected. Data is reviewed, assumptions are challenged, and results are compared against the original plan. Finally, in Act, successful changes are standardized and documented, while unsuccessful ones inform the next cycle of experimentation.

This same logic applies beyond manufacturing. A healthcare clinic might use PDCA to pilot a new patient intake workflow, reviewing wait-time data and staff feedback before refining documentation or staffing patterns. An office team might test a new meeting format, evaluate engagement and outcomes, and adjust based on what they learn. In each case, PDCA provides structure without slowing progress, enabling improvement through evidence and iteration.

Tools That Support the PDCA Cycle

PDCA does not require specialized tools to be effective, but the right tools can make each phase clearer, more disciplined, and easier to repeat. Rather than defining PDCA itself, these tools support the thinking and learning that occur within the cycle.

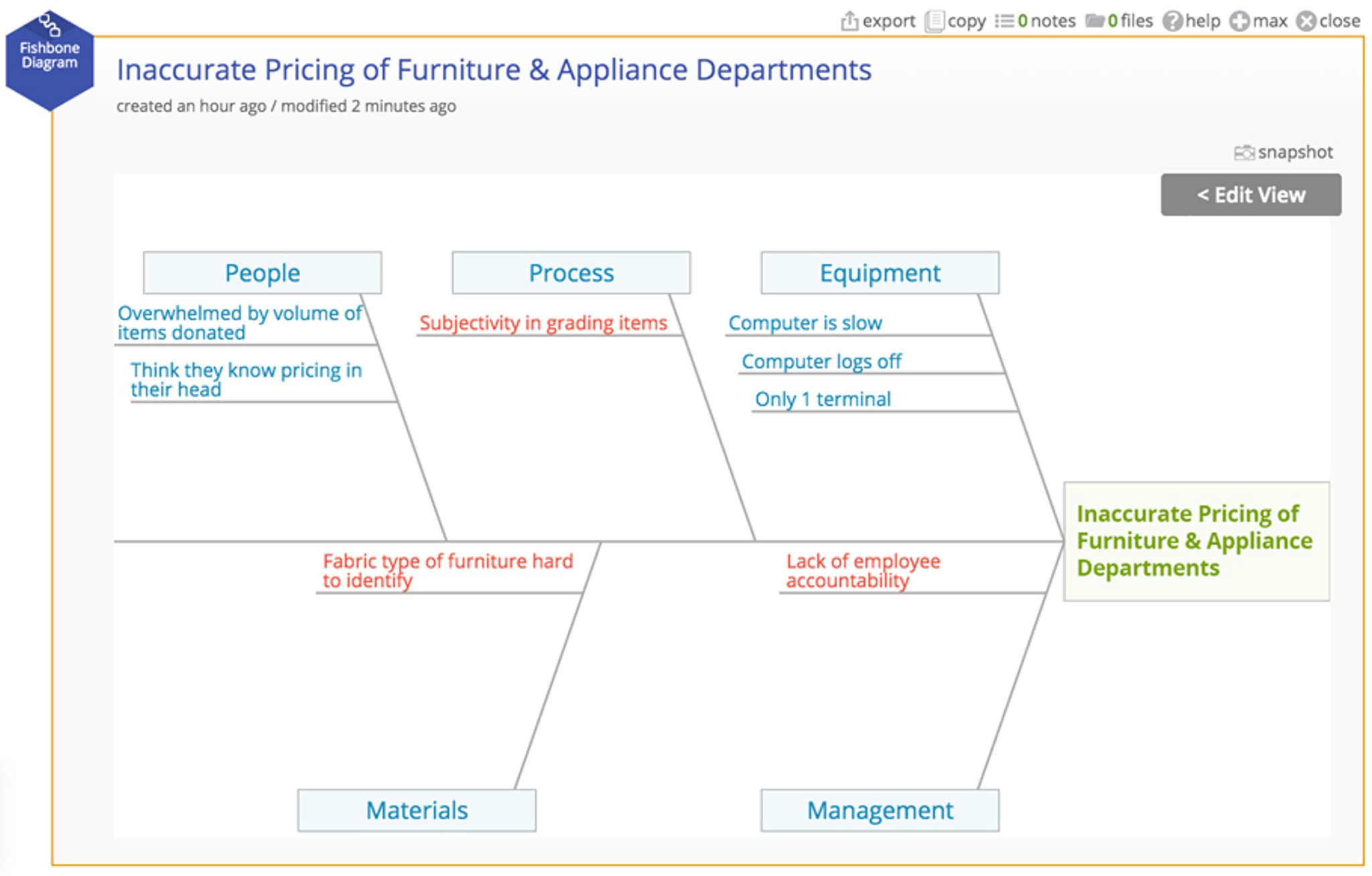

During the Plan phase, teams often use process maps, SIPOC diagrams, or cause-and-effect (fishbone) diagrams to clarify the problem, understand the current state, and form hypotheses about potential improvements. These tools help ensure that changes are intentional rather than reactive.

In the Do phase, simple pilot plans, checklists, or draft versions of standard work help teams test changes in a controlled way. The goal is not perfection, but consistency, so results can be meaningfully evaluated.

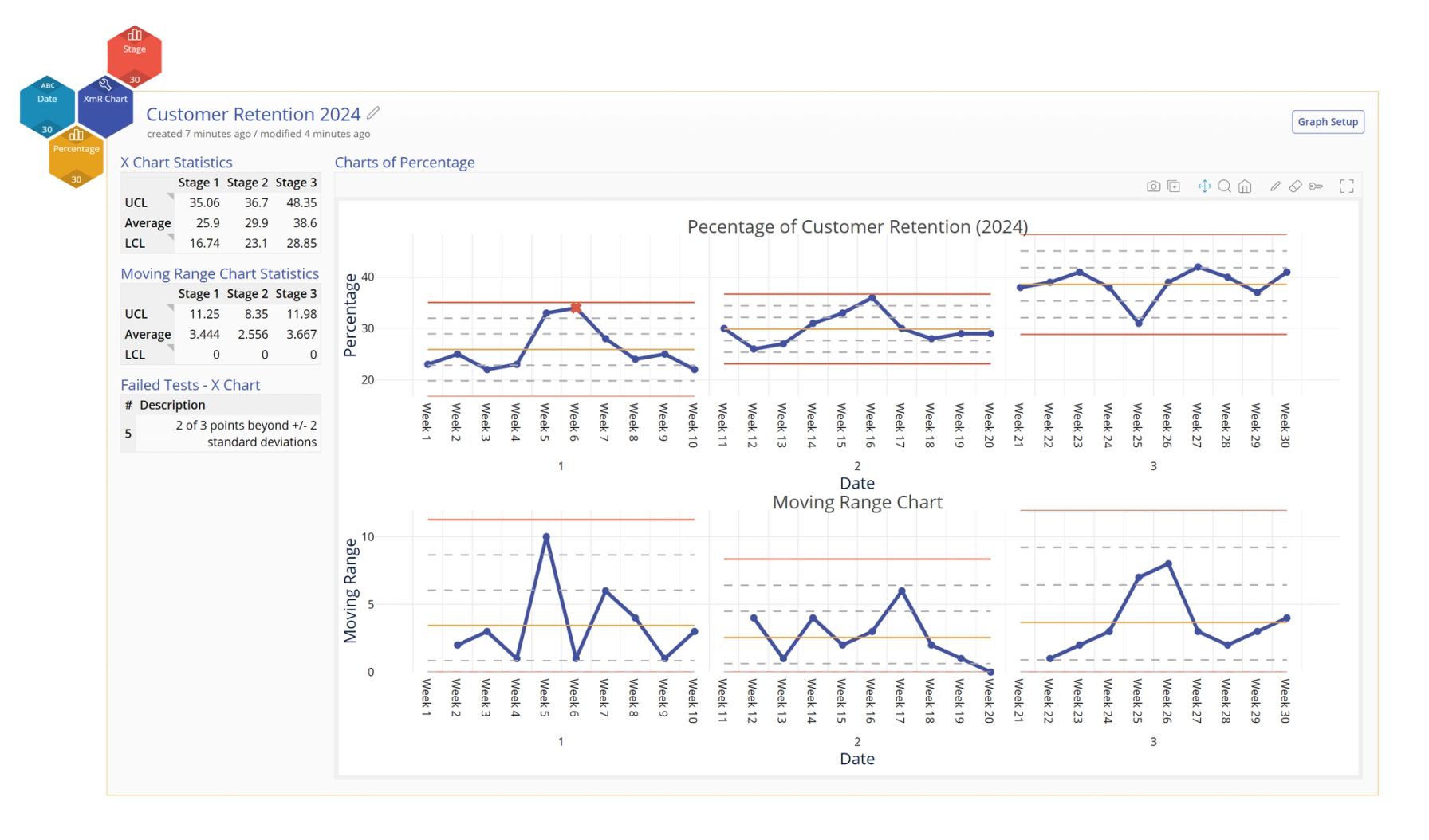

The Check phase relies on tools that make outcomes visible. Control charts, dashboards, and before-and-after comparisons help teams assess whether a change produced the expected results and whether observed variation is meaningful or simply noise.

Finally, in the Act phase, successful changes are reinforced through updated procedures, training materials, and documentation. When results fall short, what was learned informs the next PDCA cycle rather than being treated as failure.

Across all phases, the specific tools matter less than the discipline of using them to support learning, reflection, and informed decision-making.

Final Thoughts

PDCA endures because it works. Its strength lies not in complexity, but in its focus on learning, evidence, and iteration. Whether used informally by a team or formally within an improvement program, PDCA provides a reliable way to turn ideas into sustainable improvement.

Sources and Further Reading

The concepts discussed in this article are grounded in decades of research on quality, systems thinking, and continuous improvement. The following resources provide historical context and deeper insight into PDCA and its evolution:

- W. Edwards Deming Institute — Circling Back: Clearing Up Confusion About PDSA and PDCA Explores the origins of the improvement cycle and clarifies common misunderstandings surrounding PDCA and PDSA.

- W. Edwards Deming — Out of the Crisis A foundational work on quality improvement and systems thinking that shaped modern interpretations of PDCA and PDSA.

- Walter A. Shewhart — Statistical Method from the Viewpoint of Quality Control Introduces early concepts of statistical control and iterative learning that influenced the development of PDCA.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement — Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Worksheet. The IHI’s official PDSA worksheet provides a structured template and guidance for documenting and testing iterative changes as part of a continuous improvement cycle. IHI’s Model for Improvement places the PDSA cycle at the heart of improvement science.

- Walter A. Shewhart — Biographical and historical analysis (NIH / PubMed Central) Provides academic context for Shewhart’s role in the evolution of quality and improvement science.

Software Developer, CSSYB • MoreSteam

Jennifer joined MoreSteam in the fall of 2022 as a Software Developer. A certified Lean Six Sigma Yellow Belt, she brings a creative problem-solving mindset to everything she builds. Jennifer partners with the marketing team to design and develop new web pages, interactive tools, and digital experiences that help tell MoreSteam’s story in fresh and engaging ways.

Before joining MoreSteam, Jennifer spent more than a decade in photography and visual storytelling before discovering a new creative outlet in code. She completed the We Can Code IT bootcamp to earn her software development certificate and now blends her artistic eye with a knack for structured problem-solving. Jennifer graduated from the Columbus College of Art and Design with a B.F.A. in Still-Based Media Studies.