Resources for Operational Excellence

The Top 5 EngineRoom Features That Make Data Analysis Easy

Read More

Descriptive Statistics Don't Tell the Whole Story

Read More

Control Charts: The Key Tool for Process Improvement

Read More

Mastering Destructive Gauge R&R

Read More

The Future of RCA: Machine Learning-Driven Root Cause Discovery

Read More

Unlocking the Power of Statistical Hypothesis Testing: A Fresh Approach

Read More

Voices in OpEx

- Episode 10: Why Omar Mora Hates Waste and Loves Continuous Improvement

- Value Stream Maps to Value Stream Thinking as a Daily Habit

- Episode 41: Simulating Success with Dr. Lars Maaseidvaag

- How to Apply Lean Thinking to Businesses of Any Size

- Episode 34: Behavior Is the Lean Advantage with Drew Locher

- Using Process Modeling to Reduce Emergency Department Turnaround Time – Connecting Patients with Doctors Faster

Teaching Continuous Improvement

- Effectiveness of the Blended Learning Model

- Making A3 Problem Solving Accessible, Actionable, and Real

- 4 Keys to Making Your Virtual Study Halls a Success

- Beyond the Body of Knowledge: Lean Six Sigma Training for Real-World Capability

- Keeping Up: Pacing Teaching Methods with Technology

- Building a Thriving Community of Problem‑Solvers

- Making recertification work for, not against, your organization

Operational Excellence

- A Voyage of Continuous Improvement: Transforming Operations at Mercy Ships

- Sustainable Training Routines for Operational Excellence

- Making Your Strategy Work Across Your Entire Organization

- Trust Equity: The Human Side of Operational Excellence

- 'Fresh Eyes' Fuel Gains for Habitat for Humanity

- Episode 2: Building Businesses and Teams with Rich Razgaitis

Lean Thinking

- Driving Strategic Alignment with the Lean Management System

- Episode 27: Managing on Purpose with Mark Reich

- Lean Leadership Habits That Drive Organizational Excellence

- Lean Thinking: The Most Important Leadership Skill that Your Kids Don't Know

- Episode 36: Making Things Better For Everyone with Josh Howell

- Five keys to coaching Lean virtually

Project Management

- Aurorium’s TRACtion Success – From Spreadsheets to a Single Source of Truth

- Maximize Project Impact with the Right Lean Six Sigma Project Tracking Tool

- The Perfect Pair: Lean Six Sigma Project Management with Traction & EngineRoom

- Best Practices of Lean Six Sigma Project Management and Tracking Tools

- 900 Project Charters and Counting

- How TRACtion Solves 5 Common Project Management Challenges

Data Analysis & Statistics

- Why Every Continuous Improvement Practitioner Should Understand Monte Carlo Simulation

- Making Sense of Power & Sample Size

- Understanding Process Capability in Real-World Applications

- A Senior Engineer’s Clever Approach to Sampling Large Datasets

- First Things First: Verifying Assumptions Before Hypothesis Testing

- Modeling Risk with Confidence Using Monte Carlo Simulation

Upcoming Events

Lean Six Sigma Resources for Continuous Improvement and Operational Excellence

Welcome to MoreSteam's Lean Six Sigma Resource Library—a curated hub of content for professionals focused on process improvement, operational excellence, and continuous learning. Whether you're starting your Lean Six Sigma journey or advancing an enterprise-wide initiative, this page offers a diverse collection of tools and insights to help you solve problems and drive measurable impact.

Explore expert-led webinars, in-depth case studies, white papers, blogs, and podcasts—all designed to help you apply Lean Six Sigma principles in real-world settings. Learn how organizations across industries are using tools like value stream mapping and root cause analysis to reduce waste and improve quality. From foundational concepts to emerging trends in AI and digital transformation, these Lean Six Sigma resources support your growth as a problem-solver and leader in operational excellence. Whether you're looking for inspiration, training, or tactical guidance, the MoreSteam Resource Library is your go-to destination.

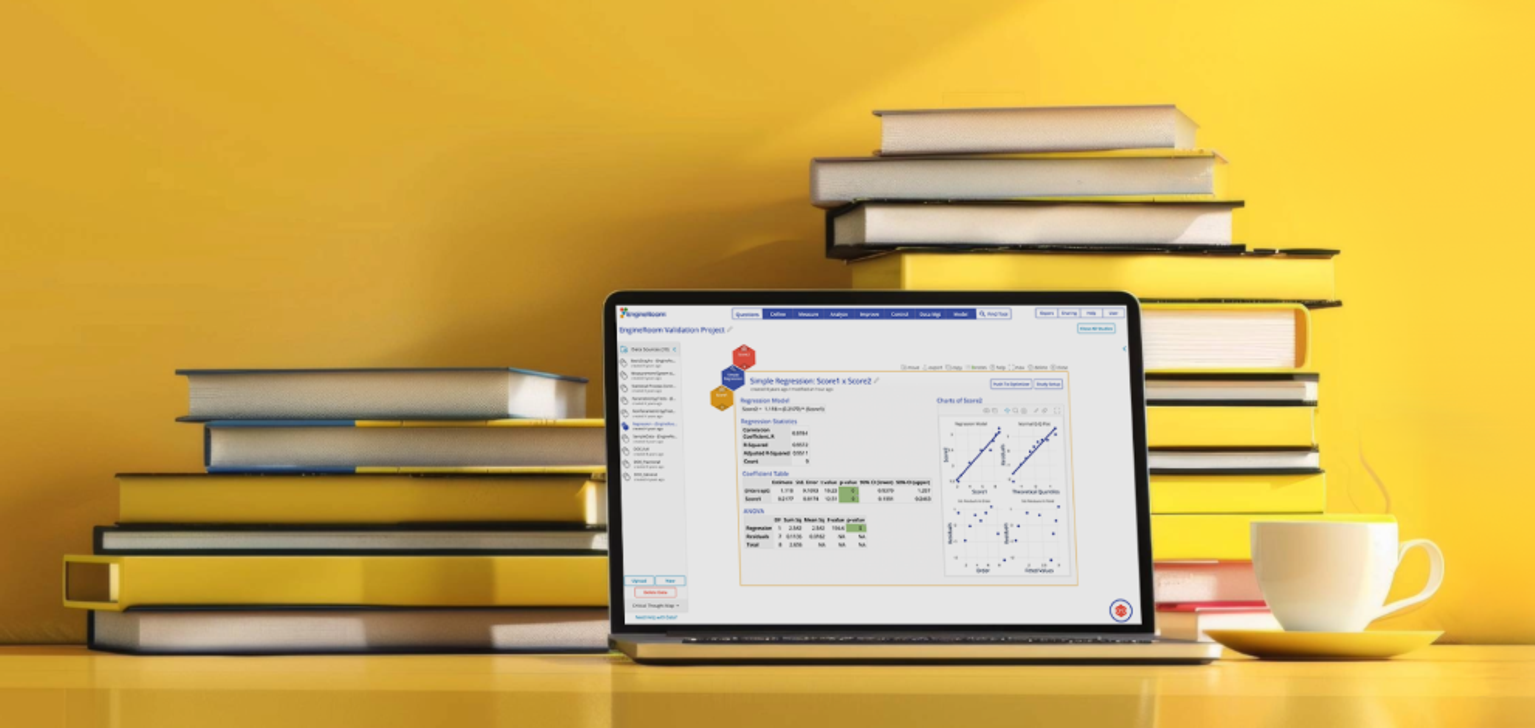

Many of these Lean Six Sigma resources also feature tools developed by MoreSteam, such as EngineRoom for data analysis and TRACtion for project tracking. Whether you're validating a process map or leading a team through DMAIC, these OpEx resources provide practical support for continuous improvement.