Is Continuous Improvement in our DNA?

November 8, 2019The Evolution from Time and Motion Studies

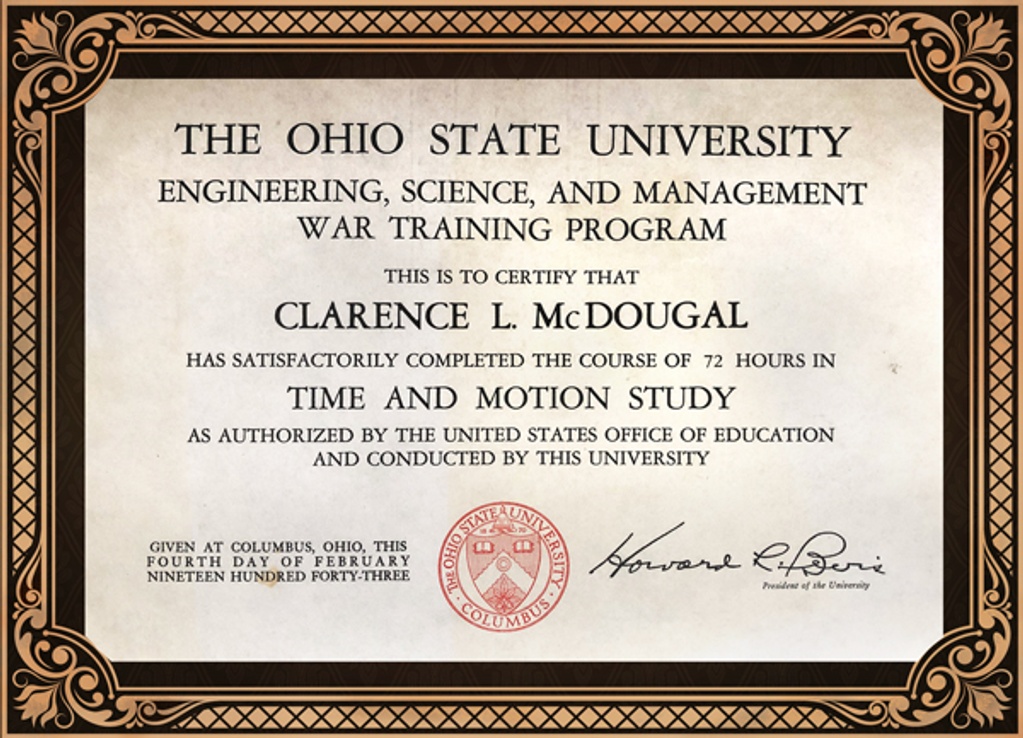

With all the new tools available for exploring your ancestry, I've become more interested lately in my heritage. That interest turned into a full‐blown passion when I ran into a cousin last summer who had traced some of our family tree back to the early 1700s. Combining our respective research, we were able to find even more information ‐ but there were still some bare branches. This sent me digging through family documents my parents and I had saved and collected over the years, all pieces of a jigsaw puzzle that slowly began forming a clearer picture of my family. One document in particular struck this industrial engineer's curiosity: a certificate from The Ohio State University showing that my grandfather had completed a course in Time and Motion Studies in 1943 as part of the War Training Program.

I learned that my grandfather had worked at manufacturer Curtiss Wright during World War II, helping improve output in support of the war effort. Based on the research that suggests our genes can influence our identity, I guess I shouldn't have been surprised that someone in my family tree actually worked to improve processes. Maybe my career in continuous improvement had been determined long before I was born.

The certificate got me thinking though about how different process improvement must have been for my grandfather. The Time and Motion Studies body of knowledge he spent 72 hours learning is only a fraction of today's Lean Six Sigma methodology. In fact, we cover the topics required for a transactional Green Belt certification in that same timespan! But my grandfather didn't have any of the data collection and analysis tools we do. Think about the challenges of drawing any conclusions about data without having even a calculator, much less a laptop and EngineRoom to help.

While my grandfather was lucky to have a shared purpose in the war effort, the production floor culture also was much different than today's. Workers often bristled at Frederick Taylor's principles of Scientific Management, which dictated that leaders should plan standard work and tell workers what to do. That's worlds away from today's continuous improvement approaches, which promote the involvement of front-line employees at every step. Respect for people is one of the pillars of the Toyota Way.

At the same time, some things haven't changed in the world of continuous improvement over more than three-quarters of a century. Taylor's principles evolved, but the need to balance the work of data analysis with the work of culture change didn't. Taylor's principles were the first foray into using data and science for understanding, then translating that information into how work was done differently. Even as experts like Deming have developed these principles and trailblazers like Toyota have applied and sharpened them, we're still working to improve that leap from data to day-to-day change. And we're still tasked with communicating in a way that drives buy‐in.

We may not have the same top-down, command-and-control cultural challenges of my grandfather's time, but change management remains one of the hardest things for any Belt or Lean leader. The case for change still must overcome the perception of being yet another "flavor of the month" that people can outlast. Convincing our employees to work in a new way, and making sure they have the necessary skill sets to do that, continues to be a big part of our jobs. Today, our jobs also involve seeking to understand what's next in continuous improvement as technology revolutionizes how we work and solve problems. Yet again, the core process is still the same: use data to understand, translate that to new ways to work, and help people prepare for change.

Were my grandfather to get a glimpse at today's continuous improvement world, I'm sure he'd be overwhelmed: workers swiping badges to record processing time, tiny RFID tags tracking flow, the rise of blockchain technology. At the same time, I think he'd be excited by the possibilities that lie ahead in the world of continuous improvement, yet another trait we share.

- Sheryl Vogt | Vogt Consulting, Inc.

MoreSteam's Enterprise Process Improvement platform includes the tools, training, and software you need to transform your organization, large or small, into a problem-solving powerhouse. Our products are trusted by over half of the Fortune 500 and by other organizations and universities worldwide. When you partner with MoreSteam you gain a team dedicated to helping you succeed.